Thank you for agreeing to appear on my blog, Judith.

Thank you, Madalyn, it’s great to be here

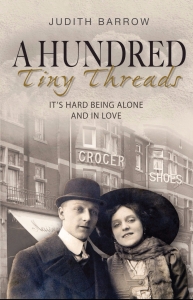

Can you tell me about your novels – in particular, your latest, A Hundred Tiny Threads?

Well, my books are a family saga trilogy set around the lives of one main family, the Howarth’s, and they span over two decades. The protagonist is Mary Howarth who has two brothers, Tom, who is an imprisoned Conscientious Objector and Patrick, a reluctant Bevan Boy involved in black marketing. She also has a younger sister, the flighty, Ellen. And then there are the parents, Winifred and Bill.

I think of them as both love stories and life stories but they have been described as gritty. Some reviewers say they evoke a sense of time and place, others that they deal with issues that spread across the generations. They are the stories of the characters’ lives at a certain time and they move between the settings of a town, Ashford, in Lancashire, and a village, Llamroth, in Pembrokeshire.

In the centre of Ashford, is a disused cotton mill, the Granville, which, in the first of the trilogy, Pattern of Shadows, has been transformed into a German POW camp during the Second World War. I suppose, in a way, the camp is a character in itself as, throughout the books, so much revolves around it. The lives of many of the characters are affected either directly or indirectly by this building, its rooms and corridors, its cellars, outbuildings and surroundings. In Pattern of Shadows it’s where two nations are thrown together, confined in enmity. It’s where Mary Howarth works as a civilian nurse in the hospital attached to the camp. It’s where fraternisation would be extremely dangerous.

Then in the sequel, Changing Patterns, set in 1950/51, with the mill no longer used as a POW camp it becomes a prison of a different sort for one character. And, yet again, it affects the lives of all the Howarth clan who, despite all their differences and rivalries, are forced to work together against a common enemy.

By the time of Living in the Shadows, 1969, the Granville is derelict but still has a capacity to become the setting for both chaos and disaster. In this book the next generation has to deal with the actions of the previous one.

The latest novel, A Hundred Tiny Threads, is actually the prequel to the trilogy. I wrote it because I wanted to show how the parents, Winifred and Bill, became the characters portrayed in Pattern of Shadows. So this one is set between 1911 and 1922, a time of turmoil, of the First World War, the Suffragette movement, the time of the great influenza epidemic and the formation of the infamous Black and Tans, sent to Southern Ireland to quell the uprising of the Irish people in their fight for Independence from the UK.

I loved, Pattern of Shadows, Changing Patterns, and Living in the Shadows. It’s interesting characters that keep me reading a book. Unique stories too, which your books are, but for me characters must have depth, they must be real. Your characters are richly drawn and very real. I felt early on in Pattern of Shadows that I knew them. I understood Mary and Peter (I won’t give spoilers), even Frank. My question is, how do you keep the essence of the characters as time passes and they get older and their lives change?

Something I always say is that we become the people we are through the lives we lead, through the things that happen to and around us as much as our inherent personalities. It’s inevitable that we change, evolve, adapt. I’ve lived with these characters in the trilogy (and the prequel) for ten years; I know them inside out and how they will react to circumstances and the changing world. At the core of each their basic personalities stay but they are all multi-layered and inevitably subtly alter as the years pass.

Tell us a little about Judith the woman? How would you describe yourself?

Ah, describe myself…that’s a tough one. I’ve been married to David for forty-seven years and we have three grown up children and five grandchildren (it’s becoming more difficult to say I was a child bride the older the children become!! Haha) I have been told I’m a typical Scorpio whatever that means. But I’ve also been told I’m too trusting and I know I’m hopeless at saying no. (Which sometimes gets me into awkward situations)? I like to think I’m kind and tolerant –well I try to be. As with most authors I’m a people watcher and, I’m ashamed to say, also an eavesdropper on conversations in shops and restaurants. I was born and brought up in village at the foot of the Pennines in Yorkshire but now I’m truly settled and content in the lovely county of Pembrokeshire where we have lived for almost forty years. I’m not good in crowds so I loved the isolation of the moors and in Wales, I love the openness of the skies and the wonderful coastline.

Judith, when and how you did you begin writing?

I can’t remember a time when I didn’t write. I was quite a solitary child and read a lot. We had a dog and I would go on long walks with her and make up different endings to some of the books I’d read. She was a good listener! I do know that I wrote long–very long stories on any topic we were set in school. When I look back I pity the poor English teachers wading through them. And I remember if a word didn’t fit or feel right for what I wanted to say I would make one up. As I say– pity the poor teachers.

And what drew you to write about life in the war?

Having had an interest in recent history for as long as I can recall it often struck me how much drastic change and how many awful events there have been in the world over the last century. The more I researched, the more I wanted to write with that as a background. Reading and hearing of the stoicism and courage of the ordinary people who faced such atrocities and disruption made me want to write about families living under those conditions.

Would you tell us about your books, and attach a link for each one, please?

A Hundred Tiny Threads;

Amazon.co.uk: http://amzn.to/2vDiQBR

Amazon.com: http://amzn.to/2vDiQBR

Pattern of Shadows:

Amazon.co.uk: http://amzn.to/1onvi4R

Amazon.com: http://amzn.to/2aMqvbg

Changing Patterns:

Amazon.co.uk: http://amzn.to/1T8iHNR

Amazon.com: http://amzn.to/2x34cXU

Living in the Shadows:

Amazon.co.uk: http://amzn.to/2tMOts9

Amazon.com: http://amzn.to/2tFasDE

All published by http://www.honno.co.uk/

I am about to read A Hundred Tiny Threads, so without giving too much away, would you give us a taster, please?

Of course. This is a section from the middle of the book when Winifred is on a march with the Suffragettes. As yet Bill has only admired her from a distance but sees her as the girl he wants as his wife. But, as an assistant to a fish monger, and with Winifred the daughter of a middle-class shop owner, there is little chance. His instinctive bitterness is never far away…

*

‘We’ll have to keep an eye out for that lot.’ Bertie pointed with the long knife he was using to gut the cod on the wooden slab towards the street. The crowds had been building steadily all morning and now streamed past in large numbers. Most of them were women but there were quite a few blokes as well, Bill noticed.

‘There’ll be trouble, mark my words. “Votes for men under twenty-one,”’ Bertie Butterworth scoffed, reading one of the posters held aloft. ‘What do kids know about ‘ow to vote?’ He slapped another cod onto the slab and brought the knife down with a loud thud. The decapitated head fell into the large bucket underneath already full to the brim with the slime of bloodied fish guts.

They could learn, Bill thought. If somebody took the trouble to show them what’s what. He knew nowt about voting because he’d had no one to explain stuff to him but he knew what was fair and what wasn’t. And it wasn’t fair that only toffs had a say in running the country. He sniffed. And it wasn’t fair his mam had died when he was only a kid.

‘There’ll be trouble I’ve no doubt.’ Bertie shook his head. ‘Here, empty this bucket, lad.’

‘Okay.’

The men and women in the crowd looked around his age, Bill thought, turning to watch them pass while automatically wiping the white trays in the shop window. He envied them, he wouldn’t tell Bertie but he really wished he could be with them. He knew nowt about what them in Government did but he didn’t see why all men shouldn’t get to vote? If men under twenty-one did get the vote, he’d be one of them; he’d get to say who gets to be in charge of the country? He didn’t believe women should have a say though.

By dinner time the street became even more crowded; a sea of white, purple and green

And then Bill caught a glimpse of his Winifred in the middle of a line of people. She was pale, her mouth set. The others were laughing and talking but she wasn’t joining in. And next to her was that bloke.

He closed his eyes against the sudden flash of temper. His hands trembled. He leant forward into the shop window, head pressed against the glass trying to see her again but she was lost amongst the masses.

Soon the crowds dwindled until there was no one walking past. When Bill finished sluicing down the floor he swept the water out of the shop doorway and across the pavement into the gutter. He stood in the doorway listening to the chants and singing in the distance. It was as though the air vibrated with the sound. The loneliness that filled every part of him was a shock; he didn’t think he’d ever been a part of anything as much as that lot obviously were. No, he corrected himself, being down the mines were near enough; he’d been in a team there, where most blokes looked out for one another.

He crossed his arms, tucked his hands under his armpits, overwhelmed by the sudden sense of loss.

And then there was something else; a low growl. He looked upwards. Iron-grey clouds slid sluggish high in the sky, the air heavy and claggy. He shivered, the feeling of foreboding starting deep inside. It was an old habitual sensation, one he used to get down the mines when there was trouble; a sudden shift in the props, a faint hiss of methane telling them all to get out. And the last time he was below, that instant of deadly silence just before the explosion. Trouble.

*

Fascinating. I can’t wait to read it.

Would you add links so we can find you and your books, please Judith?

Website

Amazon Page

Blog

Twitter

Facebook

Pinterest

Goodreads

Google+

Linkedin